Staionarry Solutions to 2d Non Linear System

Second-order linear differential equation important in physics

A pulse traveling through a string with fixed endpoints as modeled by the wave equation.

Spherical waves coming from a point source.

A solution to the 2D wave equation

The wave equation is a second-order linear partial differential equation for the description of waves—as they occur in classical physics—such as mechanical waves (e.g. water waves, sound waves and seismic waves) or light waves. It arises in fields like acoustics, electromagnetics, and fluid dynamics. Due to the fact that the second order wave equation describes the superposition of an incoming wave and an outgoing wave (i.e. rather a standing wave field) it is also called "Two-way wave equation" (in contrast, the 1st order One-way wave equation describes a single wave with predefined wave propagation direction and is much easier to solve due to the 1st order derivatives).

Historically, the problem of a vibrating string such as that of a musical instrument was studied by Jean le Rond d'Alembert, Leonhard Euler, Daniel Bernoulli, and Joseph-Louis Lagrange.[1] [2] [3] [4] [5] In 1746, d'Alembert discovered the one-dimensional wave equation, and within ten years Euler discovered the three-dimensional wave equation.[6]

Introduction [edit]

The (two-way) wave equation is a 2nd order partial differential equation describing waves. This article mostly focuses on the scalar wave equation describing waves in scalars by scalar functions u = u (x 1, x 2, …, xn ; t) of a time variable t (a variable representing time) and one or more spatial variables x 1, x 2, …, xn (variables representing a position in a space under discussion) while there are vector wave equations describing waves in vectors such as waves for electrical field, magnetic field, and magnetic vector potential and elastic waves. By comparison with vector wave equations, the scalar wave equation can be seen as a special case of the vector wave equations; in the Cartesian coordinate system, the scalar wave equation is the equation to be satisfied by each component (for each coordinate axis, such as the x-component for the x-axis) of a vector wave without sources of waves in the considered domain (i.e., a space and time). For example, in the Cartesian coordinate system, for as the representation of an electric vector field wave in the absence of wave sources, each coordinate axis component (i = x, y, or z) must satisfy the scalar wave equation. Other scalar wave equation solutions u are for physical quantities in scalars such as pressure in a liquid or gas, or the displacement, along some specific direction, of particles of a vibrating solid away from their resting (equilibrium) positions.

The scalar wave equation is

where c is a fixed non-negative real coefficient.

Using the notations of Newtonian mechanics and vector calculus, the wave equation can be written more compactly as

where the double dot denotes double time derivative of u, ∇ is the nabla operator, and ∇2 = ∇ · ∇ is the (spatial) Laplacian operator (not vector Laplacian):

An even more compact notation sometimes used in physics reads simply

where all operators are combined into the d'Alembert operator:

A solution of this equation can be quite complicated, but it can be analyzed as a linear combination of simple solutions that are sinusoidal plane waves with various directions of propagation and wavelengths but all with the same propagation speed c. This analysis is possible because the wave equation is linear; so that any multiple of a solution is also a solution, and the sum of any two solutions is again a solution. This property is called the superposition principle in physics.

The wave equation alone does not specify a physical solution; a unique solution is usually obtained by setting a problem with further conditions, such as initial conditions, which prescribe the amplitude and phase of the wave. Another important class of problems occurs in enclosed spaces specified by boundary conditions, for which the solutions represent standing waves, or harmonics, analogous to the harmonics of musical instruments.

The wave equation is the simplest example of a hyperbolic differential equation. It, and its modifications, play fundamental roles in continuum mechanics, quantum mechanics, plasma physics, general relativity, geophysics, and many other scientific and technical disciplines.

Wave equation in one space dimension [edit]

The wave equation in one space dimension can be written as follows:

This equation is typically described as having only one space dimension x, because the only other independent variable is the time t. Nevertheless, the dependent variable u may represent a second space dimension, if, for example, the displacement u takes place in y-direction, as in the case of a string that is located in the xy –plane.

Derivation of the wave equation [edit]

The wave equation in one space dimension can be derived in a variety of different physical settings. Most famously, it can be derived for the case of a string that is vibrating in a two-dimensional plane, with each of its elements being pulled in opposite directions by the force of tension.[7]

Another physical setting for derivation of the wave equation in one space dimension utilizes Hooke's Law. In the theory of elasticity, Hooke's Law is an approximation for certain materials, stating that the amount by which a material body is deformed (the strain) is linearly related to the force causing the deformation (the stress).

From Hooke's law [edit]

The wave equation in the one-dimensional case can be derived from Hooke's Law in the following way: imagine an array of little weights of mass m interconnected with massless springs of length h. The springs have a spring constant of k:

![]()

Here the dependent variable u(x) measures the distance from the equilibrium of the mass situated at x, so that u(x) essentially measures the magnitude of a disturbance (i.e. strain) that is traveling in an elastic material. The forces exerted on the mass m at the location x + h are:

The equation of motion for the weight at the location x + h is given by equating these two forces:

where the time-dependence of u(x) has been made explicit.

If the array of weights consists of N weights spaced evenly over the length L = Nh of total mass M = Nm , and the total spring constant of the array K = k/N we can write the above equation as:

Taking the limit N → ∞, h → 0 and assuming smoothness one gets:

which is from the definition of a second derivative. KL 2/M is the square of the propagation speed in this particular case.

1-d standing wave as a superposition of two waves traveling in opposite directions

Stress pulse in a bar [edit]

In the case of a stress pulse propagating longitudinally through a bar, the bar acts much like an infinite number of springs in series and can be taken as an extension of the equation derived for Hooke's law. A uniform bar, i.e. of constant cross-section, made from a linear elastic material has a stiffness K given by

where A is the cross-sectional area and E is the Young's modulus of the material. The wave equation becomes

AL is equal to the volume of the bar and therefore

where ρ is the density of the material. The wave equation reduces to

The speed of a stress wave in a bar is therefore √ E/ρ .

General solution [edit]

Algebraic approach [edit]

The one-dimensional wave equation is unusual for a partial differential equation in that a relatively simple general solution may be found. Defining new variables:[8]

changes the wave equation into

which leads to the general solution

or equivalently:

In other words, solutions of the 1D wave equation are sums of a right traveling function F and a left traveling function G. "Traveling" means that the shape of these individual arbitrary functions with respect to x stays constant, however the functions are translated left and right with time at the speed c. This was derived by Jean le Rond d'Alembert.[9]

Another way to arrive at this result is to note that the wave equation may be "factored" into two One-way wave equations:

As a result, if we define v thus,

then

From this, v must have the form G(x + ct), and from this the correct form of the full solution u can be deduced.[10] Beside the mathematical decomposition of the 2nd order wave equation the One-way wave equation can also be directly derived from the impedance.[11]

For an initial value problem, the arbitrary functions F and G can be determined to satisfy initial conditions:

The result is d'Alembert's formula:

In the classical sense if f (x) ∈ Ck and g(x) ∈ C k−1 then u(t, x) ∈ Ck . However, the waveforms F and G may also be generalized functions, such as the delta-function. In that case, the solution may be interpreted as an impulse that travels to the right or the left.

The basic wave equation is a linear differential equation and so it will adhere to the superposition principle. This means that the net displacement caused by two or more waves is the sum of the displacements which would have been caused by each wave individually. In addition, the behavior of a wave can be analyzed by breaking up the wave into components, e.g. the Fourier transform breaks up a wave into sinusoidal components.

Plane wave eigenmodes [edit]

Another way to solve the one-dimensional wave equation is to first analyze its frequency eigenmodes. A so-called eigenmode is a solution that oscillates in time with a well-defined constant angular frequency ω, so that the temporal part of the wave function takes the form e −iωt = cos(ωt) − i sin(ωt), and the amplitude is a function f (x) of the spatial variable x, giving a separation of variables for the wave function:

This produces an ordinary differential equation for the spatial part f (x):

Therefore:

which is precisely an eigenvalue equation for f (x), hence the name eigenmode. It has the well-known plane wave solutions

with wave number k = ω/c .

The total wave function for this eigenmode is then the linear combination

where complex numbers A, B depend in general on any initial and boundary conditions of the problem.

Eigenmodes are useful in constructing a full solution to the wave equation, because each of them evolves in time trivially with the phase factor . so that a full solution can be decomposed into an eigenmode expansion

or in terms of the plane waves,

which is exactly in the same form as in the algebraic approach. Functions s ±(ω) are known as the Fourier component and are determined by initial and boundary conditions. This is a so-called frequency-domain method, alternative to direct time-domain propagations, such as FDTD method, of the wave packet u(x, t), which is complete for representing waves in absence of time dilations. Completeness of the Fourier expansion for representing waves in the presence of time dilations has been challenged by chirp wave solutions allowing for time variation of ω.[12] The chirp wave solutions seem particularly implied by very large but previously inexplicable radar residuals in the flyby anomaly, and differ from the sinusoidal solutions in being receivable at any distance only at proportionally shifted frequencies and time dilations, corresponding to past chirp states of the source.

Scalar wave equation in three space dimensions [edit]

Swiss mathematician and physicist Leonhard Euler (b. 1707) discovered the wave equation in three space dimensions.[6]

A solution of the initial-value problem for the wave equation in three space dimensions can be obtained from the corresponding solution for a spherical wave. The result can then be also used to obtain the same solution in two space dimensions.

Spherical waves [edit]

The wave equation can be solved using the technique of separation of variables. To obtain a solution with constant frequencies, let us first Fourier-transform the wave equation in time as

So we get,

This is the Helmholtz equation and can be solved using separation of variables. If spherical coordinates are used to describe a problem, then the solution to the angular part of the Helmholtz equation is given by spherical harmonics and the radial equation now becomes[13]

Here k ≡ ω/c and the complete solution is now given by

where h (1)

l (kr) and h (2)

l (kr) are the spherical Hankel functions.

Example [edit]

To gain a better understanding of the nature of these spherical waves, let us go back and look at the case when l = 0. In this case, there is no angular dependence and the amplitude depends only on the radial distance i.e. Ψ(r, t) → u(r, t). In this case, the wave equation reduces to

This equation can be rewritten as

where the quantity ru satisfies the one-dimensional wave equation. Therefore, there are solutions in the form

where F and G are general solutions to the one-dimensional wave equation, and can be interpreted as respectively an outgoing or incoming spherical wave. Such waves are generated by a point source, and they make possible sharp signals whose form is altered only by a decrease in amplitude as r increases (see an illustration of a spherical wave on the top right). Such waves exist only in cases of space with odd dimensions.[ citation needed ]

For physical examples of non-spherical wave solutions to the 3D wave equation that do possess angular dependence, see dipole radiation.

Monochromatic spherical wave [edit]

Cut-away of spherical wavefronts, with a wavelength of 10 units, propagating from a point source.

Although the word "monochromatic" is not exactly accurate since it refers to light or electromagnetic radiation with well-defined frequency, the spirit is to discover the eigenmode of the wave equation in three dimensions. Following the derivation in the previous section on Plane wave eigenmodes, if we again restrict our solutions to spherical waves that oscillate in time with well-defined constant angular frequency ω, then the transformed function ru(r, t) has simply plane wave solutions,

or

From this we can observe that the peak intensity of the spherical wave oscillation, characterized as the squared wave amplitude

drops at the rate proportional to 1/r 2 , an example of the inverse-square law.

Solution of a general initial-value problem [edit]

The wave equation is linear in u and it is left unaltered by translations in space and time. Therefore, we can generate a great variety of solutions by translating and summing spherical waves. Let φ(ξ, η, ζ) be an arbitrary function of three independent variables, and let the spherical wave form F be a delta function: that is, let F be a weak limit of continuous functions whose integral is unity, but whose support (the region where the function is non-zero) shrinks to the origin. Let a family of spherical waves have center at (ξ, η, ζ), and let r be the radial distance from that point. Thus

If u is a superposition of such waves with weighting function φ, then

the denominator 4πc is a convenience.

From the definition of the delta function, u may also be written as

where α, β, and γ are coordinates on the unit sphere S, and ω is the area element on S. This result has the interpretation that u(t, x) is t times the mean value of φ on a sphere of radius ct centered at x:

It follows that

The mean value is an even function of t, and hence if

then

These formulas provide the solution for the initial-value problem for the wave equation. They show that the solution at a given point P, given (t, x, y, z) depends only on the data on the sphere of radius ct that is intersected by the light cone drawn backwards from P. It does not depend upon data on the interior of this sphere. Thus the interior of the sphere is a lacuna for the solution. This phenomenon is called Huygens' principle. It is true for odd numbers of space dimension, where for one dimension the integration is performed over the boundary of an interval with respect to the Dirac measure. It is not satisfied in even space dimensions. The phenomenon of lacunas has been extensively investigated in Atiyah, Bott and Gårding (1970, 1973).

Scalar wave equation in two space dimensions [edit]

In two space dimensions, the wave equation is

We can use the three-dimensional theory to solve this problem if we regard u as a function in three dimensions that is independent of the third dimension. If

then the three-dimensional solution formula becomes

where α and β are the first two coordinates on the unit sphere, and dω is the area element on the sphere. This integral may be rewritten as a double integral over the disc D with center (x, y) and radius ct:

It is apparent that the solution at (t, x, y) depends not only on the data on the light cone where

but also on data that are interior to that cone.

Scalar wave equation in general dimension and Kirchhoff's formulae [edit]

We want to find solutions to utt − Δu = 0 for u : R n × (0, ∞) → R with u(x, 0) = g(x) and ut (x, 0) = h(x). See Evans for more details.

Odd dimensions [edit]

Assume n ≥ 3 is an odd integer and g ∈ C m+1(R n ), h ∈ Cm (R n ) for m = (n + 1)/2. Let γn = 1 × 3 × 5 × ⋯ × (n − 2) and let

then

- u ∈ C 2(R n × [0, ∞))

- utt − Δu = 0 in R n × (0, ∞)

Even dimensions [edit]

Assume n ≥ 2 is an even integer and g ∈ C m+1(R n ), h ∈ Cm (R n ), for m = (n + 2)/2. Let γn = 2 × 4 × ⋯ × n and let

then

- u ∈ C 2(R n × [0, ∞))

- utt − Δu = 0 in R n × (0, ∞)

Problems with boundaries [edit]

One space dimension [edit]

The Sturm–Liouville formulation [edit]

A flexible string that is stretched between two points x = 0 and x = L satisfies the wave equation for t > 0 and 0 < x < L . On the boundary points, u may satisfy a variety of boundary conditions. A general form that is appropriate for applications is

where a and b are non-negative. The case where u is required to vanish at an endpoint is the limit of this condition when the respective a or b approaches infinity. The method of separation of variables consists in looking for solutions of this problem in the special form

A consequence is that

The eigenvalue λ must be determined so that there is a non-trivial solution of the boundary-value problem

This is a special case of the general problem of Sturm–Liouville theory. If a and b are positive, the eigenvalues are all positive, and the solutions are trigonometric functions. A solution that satisfies square-integrable initial conditions for u and ut can be obtained from expansion of these functions in the appropriate trigonometric series.

Investigation by numerical methods [edit]

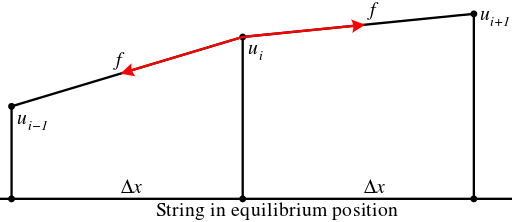

Approximating the continuous string with a finite number of equidistant mass points one gets the following physical model:

Figure 1: Three consecutive mass points of the discrete model for a string

If each mass point has the mass m, the tension of the string is f, the separation between the mass points is Δx and ui , i = 1, …, n are the offset of these n points from their equilibrium points (i.e. their position on a straight line between the two attachment points of the string) the vertical component of the force towards point i + 1 is

|

| (1) |

and the vertical component of the force towards point i − 1 is

|

| (2) |

Taking the sum of these two forces and dividing with the mass m one gets for the vertical motion:

|

| (3) |

As the mass density is

this can be written

|

| (4) |

The wave equation is obtained by letting Δx → 0 in which case ui (t) takes the form u(x, t) where u(x, t) is continuous function of two variables, ·· ui takes the form ∂2 u/∂t 2 and

But the discrete formulation (3) of the equation of state with a finite number of mass point is just the suitable one for a numerical propagation of the string motion. The boundary condition

where L is the length of the string takes in the discrete formulation the form that for the outermost points u 1 and un the equations of motion are

|

| (5) |

and

|

| (6) |

while for 1 < i < n

|

| (7) |

where c = √ f/ρ .

If the string is approximated with 100 discrete mass points one gets the 100 coupled second order differential equations (5), (6) and (7) or equivalently 200 coupled first order differential equations.

Propagating these up to the times

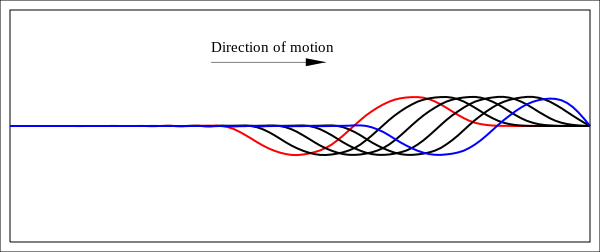

using an 8th order multistep method the 6 states displayed in figure 2 are found:

Figure 2: The string at 6 consecutive epochs, the first (red) corresponding to the initial time with the string in rest

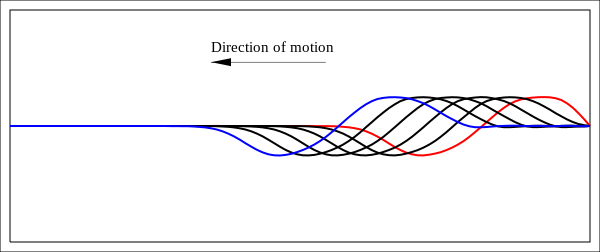

Figure 3: The string at 6 consecutive epochs

Figure 4: The string at 6 consecutive epochs

Figure 5: The string at 6 consecutive epochs

Figure 6: The string at 6 consecutive epochs

Figure 7: The string at 6 consecutive epochs

The red curve is the initial state at time zero at which the string is "let free" in a predefined shape[14] with all . The blue curve is the state at time i.e. after a time that corresponds to the time a wave that is moving with the nominal wave velocity c=√ f/ρ would need for one fourth of the length of the string.

Figure 3 displays the shape of the string at the times . The wave travels in direction right with the speed c=√ f/ρ without being actively constraint by the boundary conditions at the two extremes of the string. The shape of the wave is constant, i.e. the curve is indeed of the form f (x − ct).

Figure 4 displays the shape of the string at the times . The constraint on the right extreme starts to interfere with the motion preventing the wave to raise the end of the string.

Figure 5 displays the shape of the string at the times when the direction of motion is reversed. The red, green and blue curves are the states at the times while the 3 black curves correspond to the states at times with the wave starting to move back towards left.

Figure 6 and figure 7 finally display the shape of the string at the times and . The wave now travels towards left and the constraints at the end points are not active any more. When finally the other extreme of the string the direction will again be reversed in a way similar to what is displayed in figure 6.

Several space dimensions [edit]

A solution of the wave equation in two dimensions with a zero-displacement boundary condition along the entire outer edge.

The one-dimensional initial-boundary value theory may be extended to an arbitrary number of space dimensions. Consider a domain D in m-dimensional x space, with boundary B. Then the wave equation is to be satisfied if x is in D and t > 0. On the boundary of D, the solution u shall satisfy

where n is the unit outward normal to B, and a is a non-negative function defined on B. The case where u vanishes on B is a limiting case for a approaching infinity. The initial conditions are

where f and g are defined in D. This problem may be solved by expanding f and g in the eigenfunctions of the Laplacian in D, which satisfy the boundary conditions. Thus the eigenfunction v satisfies

in D, and

on B.

In the case of two space dimensions, the eigenfunctions may be interpreted as the modes of vibration of a drumhead stretched over the boundary B. If B is a circle, then these eigenfunctions have an angular component that is a trigonometric function of the polar angle θ, multiplied by a Bessel function (of integer order) of the radial component. Further details are in Helmholtz equation.

If the boundary is a sphere in three space dimensions, the angular components of the eigenfunctions are spherical harmonics, and the radial components are Bessel functions of half-integer order.

Inhomogeneous wave equation in one dimension [edit]

The inhomogeneous wave equation in one dimension is the following:

with initial conditions given by

The function s(x, t) is often called the source function because in practice it describes the effects of the sources of waves on the medium carrying them. Physical examples of source functions include the force driving a wave on a string, or the charge or current density in the Lorenz gauge of electromagnetism.

One method to solve the initial value problem (with the initial values as posed above) is to take advantage of a special property of the wave equation in an odd number of space dimensions, namely that its solutions respect causality. That is, for any point (xi , ti ), the value of u(xi , ti ) depends only on the values of f (xi + cti ) and f (xi − cti ) and the values of the function g(x) between (xi − cti ) and (xi + cti ). This can be seen in d'Alembert's formula, stated above, where these quantities are the only ones that show up in it. Physically, if the maximum propagation speed is c, then no part of the wave that can't propagate to a given point by a given time can affect the amplitude at the same point and time.

In terms of finding a solution, this causality property means that for any given point on the line being considered, the only area that needs to be considered is the area encompassing all the points that could causally affect the point being considered. Denote the area that casually affects point (xi , ti ) as RC . Suppose we integrate the inhomogeneous wave equation over this region.

To simplify this greatly, we can use Green's theorem to simplify the left side to get the following:

The left side is now the sum of three line integrals along the bounds of the causality region. These turn out to be fairly easy to compute

In the above, the term to be integrated with respect to time disappears because the time interval involved is zero, thus dt = 0.

For the other two sides of the region, it is worth noting that x ± ct is a constant, namely xi ± cti , where the sign is chosen appropriately. Using this, we can get the relation dx ± c dt = 0, again choosing the right sign:

And similarly for the final boundary segment:

Adding the three results together and putting them back in the original integral:

Solving for u(xi , ti ) we arrive at

In the last equation of the sequence, the bounds of the integral over the source function have been made explicit. Looking at this solution, which is valid for all choices (xi , ti ) compatible with the wave equation, it is clear that the first two terms are simply d'Alembert's formula, as stated above as the solution of the homogeneous wave equation in one dimension. The difference is in the third term, the integral over the source.

Other coordinate systems [edit]

In three dimensions, the wave equation, when written in elliptic cylindrical coordinates, may be solved by separation of variables, leading to the Mathieu differential equation.

Further generalizations [edit]

Elastic waves [edit]

The elastic wave equation (also known as the Navier–Cauchy equation) in three dimensions describes the propagation of waves in an isotropic homogeneous elastic medium. Most solid materials are elastic, so this equation describes such phenomena as seismic waves in the Earth and ultrasonic waves used to detect flaws in materials. While linear, this equation has a more complex form than the equations given above, as it must account for both longitudinal and transverse motion:

where:

- λ and μ are the so-called Lamé parameters describing the elastic properties of the medium,

- ρ is the density,

- f is the source function (driving force),

- and u is the displacement vector.

By using ∇ × (∇ × u) = ∇(∇ ⋅ u) − ∇ ⋅ ∇ u = ∇(∇ ⋅ u) − ∆u the elastic wave equation can be rewritten into the more common form of the Navier–Cauchy equation.

Note that in the elastic wave equation, both force and displacement are vector quantities. Thus, this equation is sometimes known as the vector wave equation. As an aid to understanding, the reader will observe that if f and ∇ ⋅ u are set to zero, this becomes (effectively) Maxwell's equation for the propagation of the electric field E , which has only transverse waves.

Dispersion relation [edit]

In dispersive wave phenomena, the speed of wave propagation varies with the wavelength of the wave, which is reflected by a dispersion relation

where ω is the angular frequency and k is the wavevector describing plane wave solutions. For light waves, the dispersion relation is ω = ±c | k |, but in general, the constant speed c gets replaced by a variable phase velocity:

See also [edit]

- Acoustic attenuation

- Acoustic wave equation

- Bateman transform

- Electromagnetic wave equation

- Helmholtz equation

- Inhomogeneous electromagnetic wave equation

- Laplace operator

- Mathematics of oscillation

- Maxwell's equations

- One-way wave equation

- Schrödinger equation

- Standing wave

- Vibrations of a circular membrane

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

Notes [edit]

- ^ Cannon, John T.; Dostrovsky, Sigalia (1981). The evolution of dynamics, vibration theory from 1687 to 1742. Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag. pp. ix + 184 pp. ISBN978-0-3879-0626-3.

- ^ GRAY, JW (July 1983). "BOOK REVIEWS". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. New Series. 9 (1). (retrieved 13 Nov 2012).

- ^ Gerard F Wheeler. The Vibrating String Controversy, (retrieved 13 Nov 2012). Am. J. Phys., 1987, v55, n1, p33–37.

- ^ For a special collection of the 9 groundbreaking papers by the three authors, see First Appearance of the wave equation: D'Alembert, Leonhard Euler, Daniel Bernoulli. – the controversy about vibrating strings (retrieved 13 Nov 2012). Herman HJ Lynge and Son.

- ^ For de Lagrange's contributions to the acoustic wave equation, one can consult Acoustics: An Introduction to Its Physical Principles and Applications Allan D. Pierce, Acoustical Soc of America, 1989; page 18 (retrieved 9 Dec 2012).

- ^ a b c Speiser, David. Discovering the Principles of Mechanics 1600–1800, p. 191 (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2008).

- ^ Tipler, Paul and Mosca, Gene. Physics for Scientists and Engineers, Volume 1: Mechanics, Oscillations and Waves; Thermodynamics, pp. 470–471 (Macmillan, 2004).

- ^ Eric W. Weisstein. "d'Alembert's Solution". MathWorld. Retrieved 2009-01-21 .

- ^ D'Alembert (1747) "Recherches sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration" (Researches on the curve that a tense cord forms [when] set into vibration), Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 3, pages 214–219.

- See also: D'Alembert (1747) "Suite des recherches sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration" (Further researches on the curve that a tense cord forms [when] set into vibration), Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 3, pages 220–249.

- See also: D'Alembert (1750) "Addition au mémoire sur la courbe que forme une corde tenduë mise en vibration," Histoire de l'académie royale des sciences et belles lettres de Berlin, vol. 6, pages 355–360.

- ^ http://math.arizona.edu/~kglasner/math456/linearwave.pdf.

- ^ Bschorr, Oskar; Raida, Hans-Joachim (March 2020). "One-Way Wave Equation Derived from Impedance Theorem". Acoustics. 2 (1): 164–170. doi:10.3390/acoustics2010012.

- ^ V Guruprasad (2015), "Observational evidence for travelling wave modes bearing distance proportional shifts", EPL, 110 (5): 54001, arXiv:1507.08222, Bibcode:2015EL....11054001G, doi:10.1209/0295-5075/110/54001, S2CID 42285652

- ^ Jackson, John David (14 August 1998). Classical Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 425. ISBN978-0-471-30932-1.

- ^ The initial state for "Investigation by numerical methods" is set with quadratic splines as follows: with

References [edit]

- M. F. Atiyah, R. Bott, L. Garding, "Lacunas for hyperbolic differential operators with constant coefficients I", Acta Math., 124 (1970), 109–189.

- M.F. Atiyah, R. Bott, and L. Garding, "Lacunas for hyperbolic differential operators with constant coefficients II", Acta Math., 131 (1973), 145–206.

- R. Courant, D. Hilbert, Methods of Mathematical Physics, vol II. Interscience (Wiley) New York, 1962.

- L. Evans, "Partial Differential Equations". American Mathematical Society Providence, 1998.

- "Linear Wave Equations", EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- "Nonlinear Wave Equations", EqWorld: The World of Mathematical Equations.

- William C. Lane, "MISN-0-201 The Wave Equation and Its Solutions", Project PHYSNET.

External links [edit]

- Nonlinear Wave Equations by Stephen Wolfram and Rob Knapp, Nonlinear Wave Equation Explorer by Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Mathematical aspects of wave equations are discussed on the Dispersive PDE Wiki.

- Graham W Griffiths and William E. Schiesser (2009). Linear and nonlinear waves. Scholarpedia, 4(7):4308. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.4308

Staionarry Solutions to 2d Non Linear System

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wave_equation

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}F_{\text{Newton}}&=m\,a(t)=m\,{\frac {\partial ^{2}}{\partial t^{2}}}u(x+h,t)\\F_{\text{Hooke}}&=F_{x+2h}-F_{x}=k\left[{u(x+2h,t)-u(x+h,t)}\right]-k[u(x+h,t)-u(x,t)]\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5ea668ce010e9a7afa5f5f3e22bb6e2e869143b9)

![{\displaystyle {\partial ^{2} \over \partial t^{2}}u(x+h,t)={k \over m}[u(x+2h,t)-u(x+h,t)-u(x+h,t)+u(x,t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/03475672d64f1c412bad36c0f800a70b6fec6057)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}-c{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}\right]\left[{\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}+c{\frac {\partial }{\partial x}}\right]u=0.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ad8cead9701a68a974539667b8333914f362b7b9)

![{\displaystyle \left[{\frac {d^{2}}{dr^{2}}}+{\frac {2}{r}}{\frac {d}{dr}}+k^{2}-{\frac {l(l+1)}{r^{2}}}\right]f_{l}(r)=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/62a937885ec20111868a242451a6ca6e9d7836b7)

![{\displaystyle \Psi (\mathbf {r} ,\omega )=\sum _{lm}\left[A_{lm}^{(1)}h_{l}^{(1)}(kr)+A_{lm}^{(2)}h_{l}^{(2)}(kr)\right]Y_{lm}(\theta ,\phi ),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/51bb5e70246f6db576bac408f0715d34d81641da)

![{\displaystyle u(t,x,y,z)=tM_{ct}[\phi ].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f78721e458e4493b23fdffca63665118c57908b0)

![{\displaystyle v(t,x,y,z)={\frac {\partial }{\partial t}}\left(tM_{ct}[\psi ]\right),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ab696d09a2adfb24e59f581952ecddc511b72480)

![{\displaystyle u(t,x,y)=tM_{ct}[\phi ]={\frac {t}{4\pi }}\iint _{S}\phi (x+ct\alpha ,\,y+ct\beta )\,d\omega ,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e133130561c75cecfdccb3884614ee68819e8f23)

![{\displaystyle u(x,t)={\frac {1}{\gamma _{n}}}\left[\partial _{t}\left({\frac {1}{t}}\partial _{t}\right)^{\frac {n-3}{2}}\left(t^{n-2}{\frac {1}{|\partial B_{t}(x)|}}\int _{\partial B_{t}(x)}g\,dS\right)+\left({\frac {1}{t}}\partial _{t}\right)^{\frac {n-3}{2}}\left(t^{n-2}{\frac {1}{|\partial B_{t}(x)|}}\int _{\partial B_{t}(x)}h\,dS\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d9cb9693a286a167df47269190d8f646e39a5bd6)

![{\displaystyle u(x,t)={\frac {1}{\gamma _{n}}}\left[\partial _{t}\left({\frac {1}{t}}\partial _{t}\right)^{\frac {n-2}{2}}\left(t^{n}{\frac {1}{|B_{t}(x)|}}\int _{B_{t}(x)}{\frac {g}{(t^{2}-|y-x|^{2})^{\frac {1}{2}}}}dy\right)+\left({\frac {1}{t}}\partial _{t}\right)^{\frac {n-2}{2}}\left(t^{n}{\frac {1}{|B_{t}(x)|}}\int _{B_{t}(x)}{\frac {h}{(t^{2}-|y-x|^{2})^{\frac {1}{2}}}}dy\right)\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5820790386d503931f0a6ca3236f912e5d617a1d)